This week, we offer two homilies, the first from the Council for Life of the Irish Bishops Conference and the second on the Gospel parable of the mustard seed.

Homily for Day for Life – 16th June 2024

Note: The focus for this year’s Day for Life is on how we support people who are dying with our presence and our care. The homilist will want to reflect on how the Scripture readings speak to that challenge. He would do well to weave into that reflection something of his own personal experience of accompanying parishioners through the final weeks and days of life. This is not intended to be a ready-made homily.

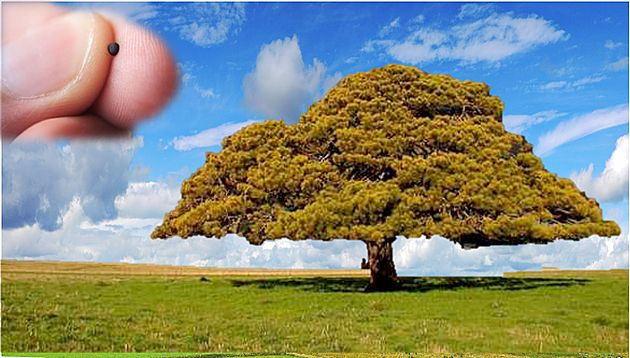

1. The experience of strength and fruitfulness. Between them, the first reading and the Gospel offer us three powerful images: (the tiny mustard seed which becomes a big shrub and provides shelter for the birds; the seed which – even in the night - produces grain and provides a plentiful harvest; and the tall imposing Cedar tree). Each of these, in its own way confidently reflects abundant life and health. This is not unlike the experience most of us have in the prime of life, when we are working hard, playing hard and building homes and families. We walk tall and we are confident.

2. There is something of a mystery underlying all this growth and vibrancy. We are told that the farmer “knows not how” the seed brings forth the grain. Is there a suggestion in here that, as St. Paul writes elsewhere, “one sows, another waters, but it is God who gives the growth”? For most of us the mystery deepens when we begin to experience, in ourselves or in others, the first signs of physical weakness and loss of energy. Perhaps there is a diagnosis of chronic or even terminal illness. What has happened to the woman or the man who, previously was so full of life and energy? Disappointment, sadness, fear, and even anger can all be part of this.

3. Doctors and nurses can achieve impressive results with the help of modern technology, but there comes a time when even they have to say that further treatment will not be of any use to the person who is sick. This news is difficult to communicate sensitively and even more difficult to receive. This is where family and friends often come into their own, with the continuing support of chaplains, nurses and doctors. The ending of treatment is not the ending of life; it is the beginning of another stage of life, when the sick person will be accompanied and cared for, physically, emotionally and spiritually. Pain relief is part of that, but there is so much more to palliative care. Often it is not so much what we do that makes the difference, but simply the fact that we are present, and that we are ready to listen.

4. [At this point the homilist might consider whether he can, without naming names, tell a personal story from his own pastoral experience, of what it means to accompany somebody who is dying. Alternatively, he might make use of the story of Matt, which is included as part of the Message for the Day for Life – click here Among the lessons which might be drawn from this human experience are:

· something about the holistic care that is provided in Hospices or at home, and which gives people freedom to live as fully as possible.

· the fact that good quality end of life care very often allows people the space to talk to family and friends in a way they haven’t done before, to heal old hurts, to come to a deeper understanding of themselves, and a deeper awareness of the closeness of God who loves them.

· that, in the experience of terminal illness, a person may, without actively choosing to die, begin to have the inner freedom to let go, and to look to eternal life. (See second reading: “we are full of confidence … and actually want to be exiled from the body and make our home with the Lord”).

· that by contrast, assisted suicide or euthanasia, far from giving people autonomy, puts a definitive end to their freedom and, with it, any possibility of growth or healing.

5. The homily might conclude by revisiting the image of the Cedar tree (first reading). What does it mean for us to say that God will take a shoot “from the highest branch” of the Cedar tree, and “plant it on the high mountain of Israel, (where) it will sprout branches and bear fruit”? Is it perhaps a way of saying that God, who seems to take the gift of life away from us, actually commits to giving it back to us again, only better than it was before. “I the Lord, am the one who stunts tall trees and makes the low ones grow, who withers green trees and makes the withered green”. God is the one in whom our deepest heart wishes are fulfilled.

HOMILY FOR ELEVENTH SUNDAY OF ORDINARY TIME (B)

Fr Billy Swan

Dear friends. In the countryside at this time of year, there are many fields of wheat and barley that are thriving. The amount of rain that has fallen in the past month along with the rise in temperature in the last week or so, has really accelerated the growth of the crops that were sown in Spring. It’s amazing to think that just a few months ago, these crops began as small seeds sowed in the ground. Slowly, they are achieving their full potential and bearing fruit by the nourishment of the soil, the energy of the sun and the spirit of life that runs through all creation. As the farmer and the gardener will tell us, there is a power of nature that is there before us that requires us to respect it’s cycles and rhythms.

This is also what Jesus points out this week with the parable of the mustard seed. We plant the seeds but the spirit of God in creation makes it grow and bear fruit. This parable is for us who can easily be discouraged. When we think that our efforts to do good are fruitless and pointless, the parable encourages us that God’s kingdom is a divine work and not a human achievement. What we do and indeed our whole lives are but tiny mustard seeds that are planted in the soil of this world. But it is God who will make them bear fruit in his own time and way.

To illustrate this ‘mustard seed principle’ I offer a few examples of mustard seeds planted in four fields around the world – one in Palestine, one in Italy and one in India.

The first seed is the life of Jesus himself in Palestine. He never wrote a book. He never held an office. He never went to college. He did none of the things we usually associated with greatness. He had no credentials but himself. Yet almost two thousand years since the seed of his life died and rose again, there are about 2.2 billion of his followers all over the world.

The second seed is the life of St Francis of Assisi. People thought he was mad as he renounced his inheritance from his father and responded to the Lord’s call that he heard at prayer from a crucifix ‘Francis, go and rebuild my Church that is falling into ruin’. Within a few years, thousands had joined the Franciscan movement that sought to live in solidarity with the poor. Only 29 years after the death of St Francis, the first Franciscans had arrived here in Wexford.

The third seed is the life of Mother Theresa of Calcutta. When she started off, she had no money, no support and no prospects of success. All she had was her desire to love and serve the poor. Yet within her lifetime, the Missionaries of Charity had founded centres all over the world dedicated to the destitute.

Friends, here are stories of seeds that had small beginnings but, in the words of today’s Gospel, grew by God’s power into shrubs with big branches. We live at a time of great change. In the midst of this change, we believe that the spirit of God is at work in it all. The spirit of new life and growth that arrived suddenly this year after a long winter is the same spirit of God that is renewing the Church and the world. May all we do and our whole lives be like those of Jesus, Francis, Mother Theresa and so many more – seeds of hope sown by God for a new harvest in the future when his kingdom comes.

‘I say to you: Make perfect your will. I say: take no thought of the harvest, But only of proper sowing’ (T.S. Eliot)

Comments